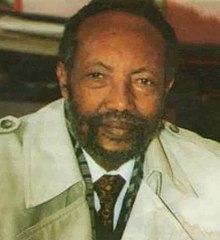

Laureat Tsegaye Gabre-Medhin (17 August 1936 – 25 February 2006) was Poet Laureate of Ethiopia, as well as a playwright, essayist, and art director.

Tsegaye Gabre-Medhin was born in Bodaa village, Ethiopia, some 120km from the capital near Ambo, to an Oromo father, who was away fighting the Italians, and an Amhara mother from North Shewa Zone. As many Ethiopian boys do, he also learned Ge'ez, the ancient language of the church, which is an Ethiopian equivalent of Latin. He also helped the family by caring for cattle. He was still very young when he began to write plays while at the local elementary school. One of those plays, King Dionysus and the Two Brothers, was staged in the presence, among others, of Emperor Haile Selassie.

Gabre-Medhin later attended the prestigious British Council-supported General Wingate school – named after British officer Orde Wingate. He subsequently attended the Commercial school in Addis Ababa, where he won a scholarship to Blackstone School of Law in Chicago in 1959. In 1960 he travelled to Europe to study experimental drama at the Royal Court Theatre in London and the Comédie-Française in Paris. Upon returning to Ethiopia, he devoted himself to managing and developing the Ethiopian National Theater – which institution staged an impressive memorial for its former director.

During this time Gabre-Medhin travelled widely; he attended the first UNESCO-organised World Festival of Black Arts in Dakar, Senegal, and the Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers. In 1966, at the age of only 29, he was awarded his country's highest literary honour, the Haile Selassie I Prize for Amharic Literature, joining the ranks of such distinguished previous recipients as Kebede Michael. The Prize earned him the title of Laureate, by which he has ever since been known.

Gebre Kristos Desta ( 1932–1981) (also Gebrekristos Desta) was an Ethiopian modern artist.[1][2] He was also known as a poet and the father of modern Ethiopian art.[3] Both his paintings and his poems unleashed waves of controversy. He died young at 50 but during his short life he transformed Ethiopian art and continues to influence today's generation of artists on many levels.Gebre was born in the town of Harrar, the son of a high ranking clergyman Aleka Desta Nego and was the youngest of six siblings. His father worked for Ras Makonnen, the governor of Harrar at the time, and was tutor to his son Ras Tafari Makonnen who was later crowned as Emperor Haile Selassie, the last emperor of Ethiopia.[4]

Gebre Kristos spent his youth on regular activities like playing soccer and volleyball he also spent a great deal of his time under his father's tutelage copying and illustrating religious manuscripts, while assisting his father as an apprentice. His early influence and introduction to art, was the traditional religious art of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.[5]

He completed his elementary education in Harrar and attended the Haile Sellassie School, and graduated from General Wingate High School. In college Desta studied agriculture, but left school early to further pursue his interest in art.[6] In 1957 he earned a scholarship to study art in Cologne, West Germany. After his graduation he held his first exhibition at the Gallery Kuppers, Cologne, it encompassed a year's work and made an extensive six-month tour of Western Europe.

Alexander "Skunder" Boghossian (July 22, 1937 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia – May 4, 2003 in Washington D.C.) was an ArmenianEthiopian painter and art teacher. He spent much of his life living and working in the United States.[1]

Boghossian was born on July 22, 1937 in Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, one and half years after the Second Italo-Abyssinian War.[1] His mother, Weizero Tsedale Wolde Tekle, was Ethiopian.[1] His father, Kosrof Gorgorios Boghossian, was a colonel in the Kebur Zabagna (Imperial Bodyguard) and of Armenian descent.[1] Kosrof's father, Gregorios Boghassian, an Armenian trader, had established a friendship with Emperor Menelik II and worked as a traveling ambassador in Europe on behalf of the Emperor.[4]

Boghossian's father was active in the resistance against the Italian occupation and was imprisoned for several years when Boghossian was a young child.[1] His mother had set up a new life apart her children and although both he and his sister Aster (Esther) visited their mother frequently, they were raised in the home of their father's brother Kathig Boghassian.[4] Kathig, who was serving as the Assistant Minister of Agriculture, together with other uncles and aunts brought them up during their father's imprisonment.[4]

He attended a traditional Kes Timhert Betoch kindergarten where he was taught the Ge'ez script.[1] In primary and secondary school, he was taught by both Ethiopian and foreign tutors and become fluent in Amharic, English, Armenian and French.[1] He studied art informally at the Teferi Mekonnen School.[5] He also studied under Stanislas Chojnacki, a historian of Ethiopian art and watercolor painter.[5]

Haddis Alemayehu (Amharic: ሀዲስ ዓለማየሁ; haddis alämayähu, 15 October 1910 – 6 December 2003), also transliterated Hadis Alamayahu, was a Foreign Minister and novelist from Ethiopia. His Amharic novel Love to the Grave (Amharic: ፍቅር እስከ መቃብር; Fəqər əskä Mäqabər, 1968) is considered a classic of modern Ethiopian literature.

He was born in the Endor Kidane Miheret section of the city of Debre Marqos, the son of an Orthodox priest, Abba Alemayehu Solomon and his mother Desta alemu. He grew up with his mother. As a boy, he began his education within the system of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, studying at the monasteries of Debre Elias, Debre Werq, and Dima Giorgis where he finally graduated in Qine (type of extended Ethiopian orthodox church education). Later, he moved to Addis Ababa where he attended several schools, including the Swedish mission school (1925–27) and later at the Tafari Makonnen School for further education of the secular sort (EthioView 12 December 2003). He wrote his first play during this period, YeHabeshan yewedehuala Gabcha (The marriage of habesha and its backwardness) which displayed remarkably mature style. In the early 1930s Hadis returned to Gojam and worked as a customs clerk and school headmaster before moving to a teaching position at Debre Markos. Haddis Alemayehu fought during the Italian-Ethiopian war for colonialism (1935–36) until he was captured and sent to the Island of Ponza in the western Mediterranean and then to the island of Lipari, near Sardinia.

Freed by allied forces Haddis finally returned to Ethiopia (1943). After brief stints in the department of Press and Propaganda and Ministry of Foreign Affaires,he became the Ethiopian consul in Jerusalem(1945–46), where he stayed for about two years.There he met and married Kibebe-tsaehay Belay,who had lived and had been brought up in Jerusalem. Haddis then served as a delegate to the international communications conference in Atlantic City, New Jersey (1946). Afterwards, he received a posting to the Ethiopian mission in Washington, D.C. and at the United Nations (1946–50). His next assignment was in the Ethiopian Foreign Ministry, first as General Director and then as Vice Minister. During the 1956–1960s he worked as Ethiopian representative to UN. After his return Haddis briefly worked at the Ministry of Education (1960) followed by appointment as Ambassador to Britain and Netherlands (1960–65).

After his recall to Ethiopia, Haddis, who was not in good health, preferred not to enter into government service. Reluctantly, he agreed to become a minister of Planning and Development (1965–66) and also served in the Ethiopian Senate (1968–74). During the era of the first two years of Derg regime (a newly brought military government taking the advantage of mass revolution), Haddis served as a member of the advisory body that had been created to replace the dissolved parliament. However he declined the Derg's offer to become Prime Minister, thus removing himself from any meaningful governmental roles. In the meantime he returned to his literature career when he published Fikr Eske Mekabr, his famous novel about love in a feudal Ethiopia. Not only this, he had written Wongelegnaw Dagna (the criminal judge) and yelemezat (sweet only in dreams) and others. He was eventually awarded an honorary doctorate by Addis Ababa University.

Baalu Girma (Amharic: በአሉ ግርማ, also rendered Be'alu) (September 22, 1939 – 1984) was an Ethiopian journalist known for his criticism of prominent members of the Derg, then Ethiopia’s socialist regime, in his book Oromay ("The End"). Girma disappeared in 1984, and it is widely believed he was abducted and killed by the Derg for his writing.[1]

Baalu Girma was born on September 22, 1939, in the province of Illiubabor, Ethiopia. His father was an Indian businessman, and his mother a local woman born to a wealthy family. His parents’ marriage ended when his father decided to move his family to Addis Ababa, and his mother’s family refused to permit them to leave. After the separation, Baalu's father continued to provide for his son; but Baalu never managed to develop a strong relationship with his father. In college, he changed his last name to Girma, after a family who took him in as their own and gave him love and care throughout his childhood in Addis.[citation needed]

Aside from being very close to his maternal grandfather and having some loving memories of one particular teacher, Baalu rarely talked about his childhood in Illiubabor. After he completed traditional Ethiopian schooling as a child, he moved to Addis Ababa and became a boarding student at the Zeneb Worq Elementary School.[citation needed]

Although he was academically very bright, as a youngster, he was also known for being a bit of a troublemaker. In fact, he was known to organize a school-wide protest in order to get his wishes.[citation needed]

Girma's excellent grades earned him a scholarship at General Wingate Secondary School. In 1951, he entered General Wingate, and it was there that he found his calling in journalism and creative writing. He often thanked his English teacher, Miss Marshall, for inspiring him and teaching him the technique of writing short sentences.[citation needed]

No comments:

Post a Comment